Thinking Less, Doing More.

Understanding the Roots of Societal Disregard for Disabled Individuals

This morning, I explored the question of why able-bodied individuals often undervalue disabled people. The response, structured with subheadings, illuminated a troubling reality: the undervaluation of disabled individuals is not only rooted in societal attitudes but is compounded by actions that perpetuate systemic exclusion. This article delves into the reasons behind these dynamics, exploring how society itself becomes a disabling force for disabled individuals.

Societal Stereotypes: A Foundation of Misconceptions

A major factor in the marginalization of disabled individuals is the persistence of societal stereotypes. These stereotypes often frame disabled people as dependent, incapable, or burdensome, leading to assumptions about their lack of ability to contribute meaningfully to society. Such perceptions create a self-reinforcing cycle: undervaluation leads to exclusion, which in turn prevents disabled individuals from proving their potential or accessing opportunities.

But this raises a critical question: if dependency is perceived as problematic, why are other groups with similar dependencies treated differently? For instance, society invests heavily in drug rehabilitation centres, mental health clinics, and other support services. These initiatives aim to empower individuals and facilitate their reintegration into society. However, such systems are often not extended to disabled individuals, whose needs are met with fragmented, underfunded, or stigmatized responses.

The Hypocrisy of Selective Support

This inconsistency highlights a troubling hypocrisy. The issue isn’t dependency itself—it’s society’s selective perception of and response to different types of dependency. For drug users or individuals with mental health conditions, dependency is often framed as a temporary hurdle deserving of robust intervention and empathy.

In contrast, disabled individuals are frequently categorized as permanently “other,” leading to systemic neglect. They are excluded from opportunities that could challenge the narrative of their supposed incapacity. This dichotomy reflects a deeper societal failure: an unwillingness to view disabled individuals as equal participants in the social and economic fabric.

Fear and Misunderstanding

Underlying much of this disparity is fear and misunderstanding. Disability challenges societal norms of productivity, independence, and physical perfection. Many able-bodied individuals are uncomfortable confronting their own vulnerability, and this discomfort often manifests as avoidance or prejudice.

Disabled people are not inherently limited by their disabilities; they are disabled by society’s barriers—physical, attitudinal, and systemic. By failing to address these barriers, society perpetuates cycles of exclusion and dependency that need not exist.

Shifting the Narrative: From Disregard to Empowerment

Breaking this cycle requires a fundamental shift in how we view disability. Rather than framing it as a deficit or burden, society must recognize the inherent value and diversity that disabled individuals bring. This includes investing in inclusive infrastructure, creating equitable opportunities, and challenging harmful stereotypes.

Empowerment begins with acknowledgment: society itself often creates the limitations that disabled people face. By addressing these limitations, we can move toward a more inclusive future where disability is no longer a reason for disregard but an opportunity for growth and collective progress.

Power does not mean ability.

Human emotions and feelings often play a critical role in shaping our understanding of power, but what is the actual value of this power when it is perceived as ineffective. The notion that a particular abled model of working and employment will inevitably lead to increased productivity and slower economic growth is not only flawed but inherently inefficient and unsustainable. Such an ideology fails to account for the nuances of local contexts and the unique challenges faced by regions like Gilgit Baltistan, where 80,000 of, us, disabled people reside

In the context of Gilgit Baltistan, where socio-economic structures are deeply rooted in cultural and geographical realities, adopting rigid, externally imposed employment or economic models can be counterproductive. While the ideology might hold theoretical merit in different scenarios, it does not align with the specific needs, resources, and aspirations of the people in this region. Instead, a more localised, inclusive, and adaptive approach is essential—one that respects the lived experiences of the community and harnesses their unique strengths for sustainable growth.

The accurate measure of a successful model lies in its ability to integrate emotional intelligence, community engagement, and practical innovation into its core, ensuring that the power wielded is meaningful, equitable, and capable of fostering genuine progress.

Evaluating Disability as a Source of Competitive Advantage

In their article, Luisa Alemany and Freek Vermeulen cite that disability should be used as a competitive advantage rather than a barrier to employment. To quote a particular case near Pakistan, Consider the Gran Estación shopping mall in Bogotá, Colombia, which employs many people with physical disabilities in a variety of roles—for example, customer relations. People who want to meet with someone in customer service are often upset and angry. Disabled employees seem better able to defuse such emotions, according to the mall’s general manager. It may be that the social model has contributed to it, but in turn, employers get more satisfied with their choices.

Colombia, like Pakistan, has an insecure political climate. It does not mean that they are violating the rights of their disabled citizens.

To what do I owe the Pleasure?

Drafting this article for this review was challenging, but it also shows that to err is to be human. Each day that we do not change this, each day, disabled people are more socially excluded, who are unused workers, that have more productivity than their non disabled counterparts. Why do we still make the same mistakes? Are we really selfish as Freud’s ID seems? Do we not want to better ourselves?

Human Nature and Feelings

I do not feel the same way as a disabled person does.

Human nature is often driven by a selfish individual perspective, with emotional feelings shaped as social constructs that reflect how an individual is perceived and behaves within society. Inside that social construct, the “I, Me, Myself” drives our inner emotions of happiness, anger, and joy.

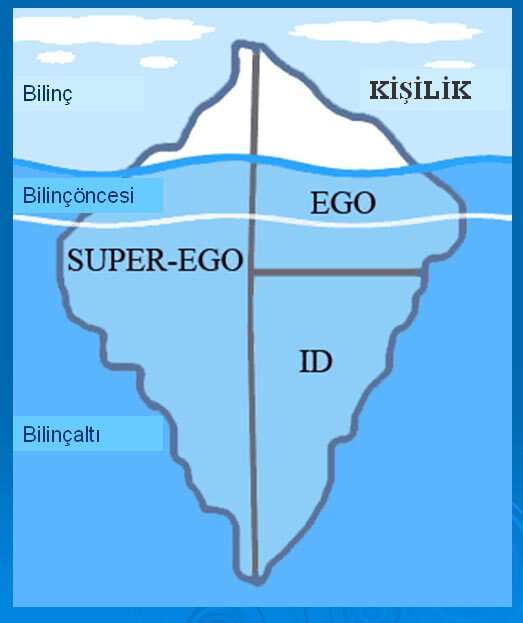

The psychologist Sigmund Freud explored this phenomenon through his theory of the human psyche, dividing it into three components: the id, ego, and superego. These components work together to influence human behavior and emotions:

- The Id:

- Represents the primal, instinctual part of the psyche.

- Operates on the pleasure principle, seeking immediate gratification for desires and needs, such as happiness and joy.

- Is inherently selfish and unconcerned with societal norms or consequences.

- The Ego:

- Acts as the rational, conscious part of the psyche.

- Balances the desires of the id with the constraints of reality and societal expectations.

- Manages inner emotions and helps navigate social constructs by aligning personal happiness with acceptable behavior.

- The Superego:

- Represents the moral conscience and internalized societal rules.

- Often in conflict with the id, as it strives for ideal behavior that aligns with cultural and ethical standards.

- Influences feelings like guilt or pride, shaped heavily by social constructs.

Freud’s framework suggests that the “I, Me, Myself” is a reflection of the ego’s negotiation between personal desires and societal expectations. Emotional states such as happiness, anger, and joy emerge as responses to this dynamic interplay. While our inner emotions may feel personal, they are often deeply rooted in the cultural and social frameworks in which we exist. We tend to think that the disabled – the less abled in some aspects of life are not influenced by this, and somehow, we tend to go into that social, medical, generous model of support.

While these emotions and feelings are valid, time and time again, to quote psychologists there are false premises that we as individuals have or keep.

Psychosis and disabled people

The Charity, Mind UK refers to Psychosis as Psychosis (also called a ‘psychotic experience’ or ‘psychotic episode’) is when you perceive or interpret reality in a very different way from people around you. Applying this to our study, it seems humanity may have entered an episodic state, failing to recognize that disabled individuals are human beings, equal in dignity and worth, rather than perceiving them as separate entities. Why?

Why, what, who and where?

Different traditions can have different contexts, but it is the WHO we are interested it in and why? One Reason is power, another reason could be fear, but more importantly it seems like that our emotions are dominated who we are. Yesterday, we had a discussion with someone, who says you and I share the same values, but it might not reflect others? While Freud’s work has been criticized as unscientific in modern psychology, it still offers valuable insights into the interplay between emotions, power, and societal constructs.

Toward a New Understanding

If we aim to break free from this episodic state, we must move beyond outdated perceptions and biases. Recognizing disabled individuals as integral members of our shared humanity requires re-examining the emotions, constructs, and power dynamics that shape our worldview. Only by doing so can we build a society that values equality, inclusivity, and mutual respect.

The Straight Path and Disabled: The Hope in the Voiceless Community

The Straight Path: A Journey Toward Justice, Compassion, and Inclusion

The concept of the “Straight Path” (Sirat-al-Mustaqeem) embodies a journey guided by justice, compassion, and equity—principles that call us to reflect on our collective responsibility to care for the most vulnerable in society. This path transcends individual growth, focusing on creating a community where everyone is uplifted and included. Yet, in the hustle of modern life, absorbed by fleeting distractions, we often lose sight of those left behind: the elderly, the disabled, and the sick. While many indulge in comfort, countless others struggle in silence.

Understanding Suffering

Suffering evokes images of famine, poverty, or war—often tied to distant regions like Africa. Yet suffering also exists in less visible, equally profound forms. In Gilgit-Baltistan, particularly in the Hunza and Yasin areas, disabled individuals live on society’s margins, yearning for dignity and inclusion. Their voices—pleas for opportunity—are often drowned by indifference. My connection to this issue deepened during my time at a community college and further intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic, as I reflected on societal norms around disability.

While certain regions in Gilgit-Baltistan have seen development through community initiatives, much remains to be done. The progress, though commendable, pales compared to the inclusivity and accessibility many of us in developed nations often take for granted.

Our Mission: The Gilgit-Baltistan Goodwill Movement (GBGM)

Through GBGM, we strive to bridge these gaps. Our mission is to create opportunities, advocate for the rights of disabled individuals, and ensure no one is forgotten. Rooted in the values of justice, compassion, and equity, our initiatives include:

- Vocational and Life Skills Training: Free programs empowering individuals to lead independent lives.

- Assistive Devices: Providing wheelchairs, hearing aids, and essential mobility tools.

- Healthcare Support: Facilitating access to free medicines and personalized care.

- Financial Aid: Addressing economic challenges by offering support for food and shelter.

- Advocacy and Awareness: Eliminating stigmas through community outreach and campaigns.

Visit www.gbgoodwillmovement.com to explore stories of resilience and transformation.

Challenges and the Way Forward

Despite progress, significant obstacles remain:

- Infrastructure Gaps: Public spaces lack accessibility for disabled individuals.

- Educational Barriers: Inclusive education opportunities are scarce.

- Healthcare Inequities: Quality, affordable healthcare remains a luxury.

- Stigma: Deep-rooted prejudices marginalize disabled individuals further.

Overcoming these challenges requires collective action and a commitment to shared humanity.

A Call to Action

Returning to the West, I hoped the lessons from the social care sector would inspire widespread support. While some have stood by us, many responses have been minimal. This underscores a pressing need: to foster connection, understanding, and action.

Imagine the loneliness of being unseen, the despair of being unheard, and the pain of being forgotten. Now, imagine that world being yours. If you can’t walk in our shoes, at least walk beside us. Offer a hand, a voice, or a moment of empathy.

Your support—whether through donations, volunteering, or spreading awareness—can transform lives. Together, we can pave the way toward a compassionate, inclusive society where everyone thrives.

The “Straight Path” requires every strand of society to unite, each bringing its unique strengths. Just as a plumber and surgeon serve vital yet distinct roles, each of us has a part in building inclusivity. Let us ensure that no voice goes unheard, no individual unseen, and no life unlived to its fullest potential.

Join us at www.gbgoodwillmovement.com

This streamlined version emphasizes clarity while preserving the inspirational tone and critical message.

Smoking The Rights of Disabled People

Introduction

Many people engage in the habit of smoking, releasing smoke into the air. Over time, the use of vapes and e-cigarettes has become so widespread in the West that it seems almost universal—young kids, teenagers, and older adults alike participate in this trend. While the act of smoking may seem harmless or insignificant to the larger world, the underlying reality reflects a different story.

For disabled individuals, the metaphorical “smoke” of this behavior symbolizes neglect. The act of smoking—releasing vapor or smoke into the air—serves no purpose beyond satisfying an individual’s craving. It mirrors the way society often overlooks the needs of disabled people, doing little to address structural barriers or create meaningful change. In this sense, just as smoking into the air is an unproductive habit, societal inaction can be similarly ineffective in tackling disability issues.

At its core, smoking and vaping are addictive behaviours driven by a craving for nicotine. Addiction can distract people from actively engaging with broader issues, including supporting those who are disabled or differently-abled. When energy is channelled into habitual, self-serving actions like smoking, it leaves little room for reflection on collective responsibility or making an impact in areas that truly matter, such as fostering inclusivity or advocating for marginalised groups.

In essence, this comparison highlights how ingrained habits—whether it’s smoking or societal indifference—can perpetuate cycles of neglect.

To break free from this, society must confront its “addiction” to complacency and instead channel its energy toward empowering and supporting those in need, such as the disabled community.

The act of doing but not saying

The Overlooked Needs of Disabled People Amid Societal Distractions

Disabled individuals face a daily struggle for visibility, resources, and inclusion. However, their needs are often overshadowed by societal behaviours and issues that, while significant in their own right, divert attention and energy away from creating systemic change

- The False Prioritization of Personal Habits Over Collective Responsibility:

Smoking, vaping, and similar habits symbolize how individuals often focus on immediate gratification or personal coping mechanisms rather than broader, more pressing societal issues. Similarly, governments and communities may prioritize addressing high-visibility concerns, like smoking-related health campaigns, while sidelining efforts to improve accessibility, promote disability rights, or reduce barriers for disabled individuals. For instance, while anti-smoking campaigns receive widespread funding and support, many disability initiatives remain underfunded and underrepresented in public discourse. - Distraction Through Debate:

Controversial issues like smoking, vaping, or other health-related behaviors dominate public debate, consuming resources and attention that could otherwise be directed toward neglected groups. For example, while legislative bodies argue over e-cigarette regulations, policies ensuring workplace accessibility or funding for disability-inclusive education languish in bureaucratic limbo. These distractions not only delay progress but also signal to disabled individuals that their concerns are not a societal priority. - The Cost of Neglect:

The financial burden of addressing smoking-related health issues is enormous, yet disability advocacy often struggles for funding. This reflects a systemic imbalance: resources are poured into mitigating self-inflicted problems like smoking while preventable barriers for disabled people—such as inaccessible infrastructure or lack of employment opportunities—are ignored. The societal cost of neglecting disability rights is immense, leading to increased dependency, unemployment, and healthcare costs for disabled individuals, which ultimately burdens society as a whole. - Reinforcement of Marginalization:

When issues like smoking dominate societal focus, they reinforce the marginalization of disabled people. The message is clear: issues impacting able-bodied individuals are deemed more urgent or important than the fundamental rights and needs of disabled people. This perpetuates cycles of exclusion, as the societal narrative consistently places other priorities above inclusivity and equity for disabled communities. - Breaking the Cycle of Neglect:

Just as smoking cessation requires intentional action to break an addictive cycle, addressing the neglect of disabled people requires a collective shift in priorities. Society must move away from reactive problem-solving, which addresses visible issues like smoking, to proactive inclusivity, which tackles the invisible struggles of marginalized groups. This shift demands a reallocation of resources, greater awareness, and a commitment to making disabled people a focal point of policymaking and societal discourse.

A Call to Action

The focus on issues like smoking symbolises a more profound truth about society’s complacency—an addiction to maintaining the status quo rather than confronting harder, less glamorous challenges like disability rights. To truly foster an inclusive society, we must challenge this complacency and redirect our collective energy and resources toward empowering disabled individuals.

The War Within – Inflicting Costs (Part one)

In previous articles, we discussed the effects, impacts, and solutions in detail. Now, I want to address a subject that delves into the psychological challenges faced by persons with disabilities. If we move persons with disabilities as objects and psychological challenges as subject, we can narrate a different story from the ableist viewpoint.

1837 to 1947 to 2017

This timeframe offers a critical lens through which to examine societal attitudes. The year 1837 marked the beginning of significant upheaval in British India, setting the stage for rebellion against colonial rule. Despite the passage of time, the psychological scars of colonialism linger, particularly in how we perceive and treat disabled individuals. Our colonial mindset, shaped by hierarchical structures and discriminatory norms, remains largely unchanged.

From the institutionalisation of disabled people during the British Raj to the continued marginalisation in post-colonial societies, the narrative around disability has often been one of exclusion and paternalism. Paternalism is a significant factor in Pakistan, but it has not shifted how we react to disabled people. It is like Katherine’s Mayo book of the Women of India, where she bragged that the Indian woman is inferior to the white man. Mayo’s book could be seen as a way of internalising how we feel about the disabled using the same terminology as the lame, dumb, deaf, blind in Pakistan even today.

The laws even remind disabled people of a colonial empire behest to work to serve the Raj not the people

Rational choice and ableism from DPOs

The rational choice we believe many make is rooted in one key question: “How convenient is this issue for me?” This stereotype-driven approach allows people to think, “I am not disabled; therefore, I won’t have these difficulties,” which creates a false sense of comfort. It is the easy way out—a mental shortcut that allows individuals to ignore the realities of ableism, reassuring themselves that these issues belong to someone else. From high-ranking officials, like a Chief Minister, down to local community leaders, this mindset sustains an illusion that dealing with disability inclusion is irrelevant to their own lives. But this notion is objectively false and contributes to a cycle of harmful inaction.

In reality, disability is not a niche issue. It is a fundamental human rights issue. Everyone, directly or indirectly, interacts with individuals facing disabilities. When leaders or decision-makers choose avoidance or indifference, they are essentially opting for convenience over justice. This mindset arguably violates the basic human rights of disabled individuals by limiting their access to opportunities, spaces, and roles within society.

By “human rights,” we mean the systemic exclusion of disabled individuals from workplaces, educational settings, and economic opportunities. In fact, a brief literature review conducted by the Goodwill Movement reveals that the economic inclusion of disabled people brings measurable benefits—higher productivity, enhanced community engagement, and strengthened social support networks. Yet, these truths remain buried under convenient excuses.

“Isn’t It Difficult?”

Another perspective that enables ableism is the idea that interacting with or including disabled individuals is inherently challenging. When we correspond with potential donors—via email, calls, or meetings—we often notice a subtle reluctance to engage fully. It feels as though many donors wish to “get through” these conversations so they can focus on something more familiar or comfortable. They seem eager to shift to another topic, to avoid exploring the profound value and necessity of true inclusion.

This brings us to a fundamental question: Are we merely servants to other’s convenience? It does feel like it many times.

Disabled individuals deserve respect and engagement, not to be merely dismissed as an “inconvenient” task. The expectation that organisations like ours must cater entirely to the preferences of potential donors instead of being met halfway shows a lack of genuine commitment towards societal change. That being said, we will commit to those donor preferences who are on the same page as us, and we have done so in the past

The cycle of trapped bias

Goodwill has been striving since 2021 to advocate for the rights and support of persons with disabilities in Gilgit Baltistan and among its global diaspora. This work aims to create lasting, collective benefits by ensuring inclusive development and resources for individuals with disabilities. Yet, why do we still encounter resistance, limited resource mobilisation, and fragmented support from within the community and diaspora? Game theory could explain this

Could this be akin to a ‘Prisoner’s Dilemma’ situation, where individual stakeholders, despite having mutual interests in the cause, prioritize short-term gains or avoid risks over collaboration? Just as in the classic dilemma, if all involved parties cooperated, the collective outcome could significantly uplift lives and strengthen the community’s social fabric. So, what factors keep stakeholders from fully investing, and how can we break this cycle to foster true, sustained support?

Objective

The objective of Goodwill is to get more donations to fund more projects. Let’s call this D and F. D and F have a crossover.

Variables

Has Goodwill launched a donation site? Yes

Has Goodwill partnered with a third sector organisation? Yes

Bias

In the classic Prisoner’s Dilemma game, Prisoners A and B have four possible outcomes based on their choices to either cooperate (stay silent) or defect (testify against each other). Similarly, in donating to a cause or supporting a cause, people have the will to stay silent or ignore it. The will here, though is not a rational one but the unconscious bias that keep’s one eyes and ears closed to reality

Power & Culture – Ableism

The term ableism refers to discrimination in favour of able-bodied people. Ableism or in Loose Urdu, the ability to physically control one’s body has been a debate over decades. But what makes ableism so unique is that what we refer to Power & Culture : ableism thrives on it. Unlike Feminism, Ableism is non gender bias and non sex biased. Yes I do agree, that sexual relations and gender identity can affect it. However as social beings, ableism is still around everywhere.

As described in a earlier article, the pathological fear of ableism thrives upon society and by that effect culture. Ableism is not something measurable, though many disabled activists like Julia Harris and other people have highlighted the negative effects of ableism : there is something about it that we like, we thrive upon not just in Pakistan but across the world. One thesis/statement is that we like to be in a powerful seat or position whereby we can other the disabled/differently abled and we feel ‘ good ‘ about it.

Sociobiological theory

Now what does it mean by good? I am not referring to a pleasurable experience although we did see effects of it in Nazi Germany, that can have a article of its own and in Pakistan, where we daily blog from but somehow the human body has developed this feeling of protection amongst foreign experience’s.

Conclusion

Is there a way that we are not looking at this properly. Is Power over the disabled rooted from our biological needs described by Maslow. Should we not address this from a socio biological viewpoint?