Category: Uncategorized

“Does the Global North Systematically Oppress Disabled Individuals in the Global South?”

International Development Lens

The Lens of Disability Development can be interpreted in multiple ways, and the unseen stories shared here represent just one dimension of this perspective. These narratives challenge conventional understandings of progress, inclusion, and agency, particularly within the framework of disability studies. However, the very notion of “development” itself is often constructed through a Western, if not explicitly Eurocentric, lens—one shaped by historical contexts, colonial legacies, and dominant economic paradigms that prioritize market-driven growth, institutional governance, and standardized policy interventions.

Institutional Frameworks and the Limits of Western Development Models

Taking Douglas North’s perspective on development, he emphasizes the role of institutions—both formal (laws, regulations) and informal (social norms, cultural beliefs)—in shaping economic and social progress. North’s analysis suggests that development is an evolutionary process, where institutions reduce uncertainty, create incentives, and guide the trajectory of societies. However, applying this framework to disability development raises critical questions:

- Whose institutions dictate what “development” looks like for persons with disabilities? Many international development policies assume a universal trajectory of progress, yet disability rights and accessibility vary significantly across cultures and economic systems.

- How do informal norms—such as societal perceptions of disability—interact with formal policies to either enable or hinder inclusion? While legal frameworks may enforce accessibility rights, social stigmas often persist, limiting real-world implementation.

- Can a development model rooted in Western economics thoughtfully capture the lived realities of people with disabilities in diverse cultural and socio-economic contexts? A model focused on GDP growth and institutional efficiency may overlook community-led, indigenous, or localized approaches to disability inclusion.

These questions highlight the need for a more inclusive, intersectional, and globally nuanced approach to development—one that transcends Western-centric assumptions and recognizes the agency of disabled individuals in shaping their own futures.

Western Agency and Congitive Dissoance

The assumption that Western nations—such as Canada, the United States, and much of Europe—have an inherent sense of civic leadership, governance, and humanitarian responsibility, while non-Western societies lack such capacities, leads to a distorted perception of global development. This perspective has roots in colonial ideology, where Western nations positioned themselves as “civilizing forces,” tasked with modernizing the so-called “developing world.”

Historians and politicians often reference the saying that “the Sun never sets on the British Empire” to underscore the vast reach and influence of Western colonial power. However, this legacy continues to shape international development today—through foreign aid, economic interventions, and policy frameworks that often prioritize Western models of governance over indigenous, communal, or non-Western systems.

For individuals who have emigrated from the Global South to Western nations, this creates a cognitive dissonance—a tension between the idealized narrative of Western progress and the lived reality of systemic inequalities, racial biases, and policy failures. While Western nations may champion disability rights and social inclusion rhetorically, the practical challenges—such as inaccessible healthcare, employment discrimination, and social exclusion—highlight the gap between policy and lived experience.

Thus, re-examining the international development lens requires moving beyond the idea that Western nations are the sole arbiters of progress. Instead, a pluralistic approach—one that values local knowledge systems, lived experiences, and non-Western traditions of social welfare—must be at the forefront of rethinking disability development and international development as a whole.

Who are we to judge?

In every city, near and far,

Live souls that shine like guiding stars.

Some may walk, some roll instead,

Yet dreams still dance within their heads.

Why shed tears in sorrow deep?

Why let pity steal your sleep?

Lift them up, help them grow,

Watch their talents brightly glow.

Teach with love, with kindness, share,

Show them that the world can care.

Don’t be lame, don’t just conform,

Blindly following societal norms.

See their strength, their will, their grace,

A world for all—our shared space.

So take their hands, don’t turn away,

Together, build a brighter day.

Hope through Goodwill – Gilgit Baltistan’s Manifesto

In his address to the Ismaili Jamat on Monday, His Highness the Aga Khan, Rahim Al Hussaini, underscored the significance of community development as a pillar of both individual well-being and global progress. He emphasized that sustainable development must be inclusive, ensuring that every individual, regardless of their circumstances, has the opportunity to contribute meaningfully to society.

The Gilgit-Baltistan Goodwill Movement (GBGM) remains deeply aligned with this vision and is steadfast in its mission to uplift and empower marginalized communities. Our commitment to social equity is rooted in the principles of inclusivity, dignity, and progress for all, particularly for disabled and differently abled individuals.

We firmly believe that accessibility and equal opportunities are fundamental human rights. Through our ongoing initiatives, we work to remove barriers—both physical and societal—that hinder full participation. By fostering an environment of understanding, support, and integration, we aim to empower individuals with disabilities to lead independent and fulfilling lives.

Our approach extends beyond advocacy; we actively implement programs that enhance accessibility in education, employment, and public spaces. We collaborate with local and international partners to drive policy changes, increase awareness, and create tangible solutions that improve quality of life.

At GBGM, we are dedicated to building a society where every individual, regardless of ability, religion, or gender, is recognized for their unique contributions. By working together, we can create a future that reflects the values of inclusion, compassion, and shared prosperity.

Empowering Voices: Hope for the Voiceless in Our Communities

Empowering Voices: Hope for the Voiceless in Our Communities

In a world where many individuals still face barriers to inclusion, a profound and thought-provoking article on Simerg titled “The Straight Path and the Disabled: Hope in the Voiceless Community” invites us to reflect on the challenges experienced by differently-abled individuals and our collective role in empowering them.

This article highlights how compassion, inclusivity, and understanding can transform lives, build unity, and foster hope for those who are often left unheard. As members of a global community, we share a responsibility to create environments where everyone—regardless of ability—can thrive.

📖 Read the full article here: https://t.ly/shortened-link

As we continue to advocate for inclusion and equality, this article serves as an inspiring reminder of the power of hope and collective action. Let us work together to make a difference—starting with awareness, dialogue, and empathy.

Join the Conversation

We’d love to hear your thoughts! How can we, as individuals and as a community, better support differently-abled individuals? Share your comments below or get in touch with us to collaborate on initiatives that foster inclusivity and empowerment.

📩 Contact Us: www.gbgoodwillmovement.com

📱 Follow Us on Social Media: https://www.facebook.com/GBGWM

A response to IsmailiMail

Statement: Addressing Misrepresentation and Dismissive Behavior by IsmailiMail

While we appreciate the initial effort to shed light on the challenges faced by differently-abled individuals then, it is essential to address the subsequent misrepresentation of our work and mission within the article. After its publication, we maintained positive relations with IsmailiMail and engaged constructively. However, following this, we have been met with accusations of having a failed marketing strategy and being unwilling to publish content on their platform, which is both inaccurate and dismissive.

These actions undermine the values of fairness, inclusion, and mutual respect that are essential for meaningful collaboration. The disregard for our contributions and the unfair portrayal of our efforts threaten to distort the public’s understanding of the work being done by the Gilgit Baltistan Goodwill Movement (GBGM).

Call for Accountability and Fair Representation

To address these concerns, we respectfully request the following actions:

- Accurate Representation: Ensure that future articles provide a truthful and balanced depiction of GBGM’s initiatives and leadership in disability inclusion.

2. Public Clarification: Acknowledge the inaccuracies and issues raised, and issue a statement that accurately reflects our work and values.

3. Constructive Dialogue: Engage with GBGM to foster an environment of openness and mutual understanding, emphasizing the importance of fairness and collaboration.

Working with Donors – Challenges and diffculties

Working with Donors: Challenges and Difficulties

Engaging with donors is vital for non-profit organizations, as they provide the financial foundation necessary to drive meaningful change. However, working with donors often comes with its own set of challenges, requiring careful planning, persistence, and the ability to align their interests with the mission of the organization.

When I started the Gilgit Baltistan’s Goodwill Movement, the primary objective was to create a platform that could effectively engage donors and rally support for a greater cause: empowering marginalized communities, especially those with disabilities, in one of the most remote and underserved regions of Pakistan. The mission was born out of the realization that the existing support systems were inadequate and that sustainable change could only be achieved through collective responsibility and the involvement of compassionate contributors.

While supporting individuals like Amjad and many others facing daily struggles, I witnessed firsthand the transformative power of donor engagement. Every contribution, no matter how small, became a lifeline for individuals who had lost hope. However, the journey was not without hurdles.

Establishing trust with donors required consistent transparency, accountability, and storytelling that highlighted the real impact of their contributions. At the same time, navigating cultural differences, limited resources, and the logistical challenges of working in a geographically isolated area often tested the resilience of the movement.

Yet, these challenges also underscored the importance of perseverance and the need for innovative approaches to donor engagement. By creating awareness through social media campaigns, fostering personal connections, and demonstrating measurable outcomes, the movement was able to inspire a growing network of supporters dedicated to uplifting the disabled community in Gilgit Baltistan.

In reflecting on this journey, it’s clear that the heart of donor engagement lies in shared values and the belief that even the smallest acts of generosity can create ripples of change.

To address this, it became clear that transforming the Gilgit Baltistan Goodwill Movement into a formal registered charity was essential. Establishing a structured and transparent framework would not only enhance credibility but also provide donors with the assurance that their contributions were being managed responsibly and effectively. A formal charity would allow us to implement rigorous accountability measures, present detailed financial reports, and demonstrate the tangible impact of their support on the ground.

This realization marked a pivotal moment for the movement. By transitioning into a formal entity, we aim to bridge the trust gap, foster stronger donor relationships, and attract sustainable funding for our initiatives.

Thinking Less, Doing More.

Understanding the Roots of Societal Disregard for Disabled Individuals

This morning, I explored the question of why able-bodied individuals often undervalue disabled people. The response, structured with subheadings, illuminated a troubling reality: the undervaluation of disabled individuals is not only rooted in societal attitudes but is compounded by actions that perpetuate systemic exclusion. This article delves into the reasons behind these dynamics, exploring how society itself becomes a disabling force for disabled individuals.

Societal Stereotypes: A Foundation of Misconceptions

A major factor in the marginalization of disabled individuals is the persistence of societal stereotypes. These stereotypes often frame disabled people as dependent, incapable, or burdensome, leading to assumptions about their lack of ability to contribute meaningfully to society. Such perceptions create a self-reinforcing cycle: undervaluation leads to exclusion, which in turn prevents disabled individuals from proving their potential or accessing opportunities.

But this raises a critical question: if dependency is perceived as problematic, why are other groups with similar dependencies treated differently? For instance, society invests heavily in drug rehabilitation centres, mental health clinics, and other support services. These initiatives aim to empower individuals and facilitate their reintegration into society. However, such systems are often not extended to disabled individuals, whose needs are met with fragmented, underfunded, or stigmatized responses.

The Hypocrisy of Selective Support

This inconsistency highlights a troubling hypocrisy. The issue isn’t dependency itself—it’s society’s selective perception of and response to different types of dependency. For drug users or individuals with mental health conditions, dependency is often framed as a temporary hurdle deserving of robust intervention and empathy.

In contrast, disabled individuals are frequently categorized as permanently “other,” leading to systemic neglect. They are excluded from opportunities that could challenge the narrative of their supposed incapacity. This dichotomy reflects a deeper societal failure: an unwillingness to view disabled individuals as equal participants in the social and economic fabric.

Fear and Misunderstanding

Underlying much of this disparity is fear and misunderstanding. Disability challenges societal norms of productivity, independence, and physical perfection. Many able-bodied individuals are uncomfortable confronting their own vulnerability, and this discomfort often manifests as avoidance or prejudice.

Disabled people are not inherently limited by their disabilities; they are disabled by society’s barriers—physical, attitudinal, and systemic. By failing to address these barriers, society perpetuates cycles of exclusion and dependency that need not exist.

Shifting the Narrative: From Disregard to Empowerment

Breaking this cycle requires a fundamental shift in how we view disability. Rather than framing it as a deficit or burden, society must recognize the inherent value and diversity that disabled individuals bring. This includes investing in inclusive infrastructure, creating equitable opportunities, and challenging harmful stereotypes.

Empowerment begins with acknowledgment: society itself often creates the limitations that disabled people face. By addressing these limitations, we can move toward a more inclusive future where disability is no longer a reason for disregard but an opportunity for growth and collective progress.

Emigration Studies and Disabled People

The purpose of migration, immigration, or emigration is, at its core, a pursuit of better socioeconomic circumstances and improved quality of life. Whether driven by financial necessity, educational aspirations, or personal growth, the act of leaving one’s homeland is inherently tied to the hope for opportunity. According to a recent report by The Friday Times, based on an analysis by Pulse Consultants titled “An Overview of Pakistani Emigration Patterns (2008-2024),” over 10 million Pakistanis have emigrated since 2008, primarily in search of work. This wave of migration has brought significant financial benefits to Pakistan, with overseas workers contributing $30.251 million in remittances.

However, while remittances offer an undeniable boost to the national economy, they also expose a more complex reality. The economic potential of a nation like Pakistan is often undermined by a reliance on remittances rather than fostering sustainable development within the country. The low economic output highlighted in yesterday’s blog suggests a broader issue: the departure of so many individuals in search of better opportunities reflects a failure to address structural inequities at home. It also reveals an undercurrent of biased ignorance or arrogance that can arise among those who leave, often unaware of—or disconnected from—the struggles of those left behind.

The Disconnected Margins

The remittance figure of $30.251 million demonstrates the tangible benefits of migration for individuals and their families. Yet, it also raises critical questions about collective responsibility. Even if migration improves individual circumstances, it does little for the marginalized populations who remain in Pakistan, particularly the disabled. By definition, the most marginalized—those lacking the financial resources, networks, or physical ability to emigrate—will always remain within the country. This includes individuals with disabilities, who often experience exclusion not just from opportunities but also from the broader narratives of progress fueled by emigration.

As emigrants settle abroad, their focus on personal and familial gains often sidelines the systemic issues back home. This ignorance or arrogance, while unintentional, becomes evident in the diaspora’s limited engagement with those who are most in need. The disabled community, already marginalized within local frameworks, suffers further from this disconnect. For them, the question becomes not just about opportunity but about survival, equity, and the recognition of their potential.

Where is Home?

For many emigrants, “home” becomes a fluid concept, defined more by where they find economic stability than where they were born. But what does “home” mean for those who cannot leave? For disabled individuals, home is both a place of belonging and a site of struggle—a space where they fight daily to prove their worth and capabilities in the face of societal biases. Their existence challenges the very notion of home as a safe or nurturing environment, as they confront barriers to education, employment, and dignity.

Disabled people, by their very nature, often possess a profound desire to outperform, to prove to the world—and to themselves—that they are just as skilled, capable, and deserving as anyone else. They harbor a quiet determination to break stereotypes and exceed expectations. Yet, this potential often goes unnoticed or unsupported, both by local systems and by overseas communities who might otherwise champion their cause.

Why Are We So Afraid?

Why, then, do we as a society shy away from embracing the contributions of the disabled? Is it fear of confronting our biases? Is it the discomfort of acknowledging that true progress requires dismantling deeply entrenched inequalities? Or perhaps it is the unwillingness to challenge the status quo, which too often defines success in narrow, able-bodied terms.

The fear may also lie within the disabled community itself—not of failure, but of a world that continually underestimates them. The courage it takes to step forward in such a world is immense, yet it is often met with apathy or resistance. For emigrants, engaging with this reality requires both humility and a willingness to confront the privilege their mobility affords them.

Bridging the Divide

To truly address the inequities left in the wake of emigration, the diaspora must redefine their understanding of home. Home is not merely where opportunity lies; it is where responsibility begins. By acknowledging the struggles of those left behind—particularly the disabled—diaspora communities can transform their remittances from transactional to transformational. This involves not just financial contributions but also advocacy, mentorship, and investment in systems that empower the marginalized.

Disabled individuals, in turn, need platforms that amplify their voices and showcase their skills. They are not mere recipients of aid but active contributors to society, capable of driving innovation, inspiring change, and redefining what it means to succeed.

In this reimagined vision of home, no one is left behind—not the emigrant chasing dreams abroad, nor the disabled person proving their worth against all odds. Together, these narratives can converge to create a world that values equity over ignorance and potential over prejudice.

Power does not mean ability.

Human emotions and feelings often play a critical role in shaping our understanding of power, but what is the actual value of this power when it is perceived as ineffective. The notion that a particular abled model of working and employment will inevitably lead to increased productivity and slower economic growth is not only flawed but inherently inefficient and unsustainable. Such an ideology fails to account for the nuances of local contexts and the unique challenges faced by regions like Gilgit Baltistan, where 80,000 of, us, disabled people reside

In the context of Gilgit Baltistan, where socio-economic structures are deeply rooted in cultural and geographical realities, adopting rigid, externally imposed employment or economic models can be counterproductive. While the ideology might hold theoretical merit in different scenarios, it does not align with the specific needs, resources, and aspirations of the people in this region. Instead, a more localised, inclusive, and adaptive approach is essential—one that respects the lived experiences of the community and harnesses their unique strengths for sustainable growth.

The accurate measure of a successful model lies in its ability to integrate emotional intelligence, community engagement, and practical innovation into its core, ensuring that the power wielded is meaningful, equitable, and capable of fostering genuine progress.

Evaluating Disability as a Source of Competitive Advantage

In their article, Luisa Alemany and Freek Vermeulen cite that disability should be used as a competitive advantage rather than a barrier to employment. To quote a particular case near Pakistan, Consider the Gran Estación shopping mall in Bogotá, Colombia, which employs many people with physical disabilities in a variety of roles—for example, customer relations. People who want to meet with someone in customer service are often upset and angry. Disabled employees seem better able to defuse such emotions, according to the mall’s general manager. It may be that the social model has contributed to it, but in turn, employers get more satisfied with their choices.

Colombia, like Pakistan, has an insecure political climate. It does not mean that they are violating the rights of their disabled citizens.

To what do I owe the Pleasure?

Drafting this article for this review was challenging, but it also shows that to err is to be human. Each day that we do not change this, each day, disabled people are more socially excluded, who are unused workers, that have more productivity than their non disabled counterparts. Why do we still make the same mistakes? Are we really selfish as Freud’s ID seems? Do we not want to better ourselves?

Human Nature and Feelings

I do not feel the same way as a disabled person does.

Human nature is often driven by a selfish individual perspective, with emotional feelings shaped as social constructs that reflect how an individual is perceived and behaves within society. Inside that social construct, the “I, Me, Myself” drives our inner emotions of happiness, anger, and joy.

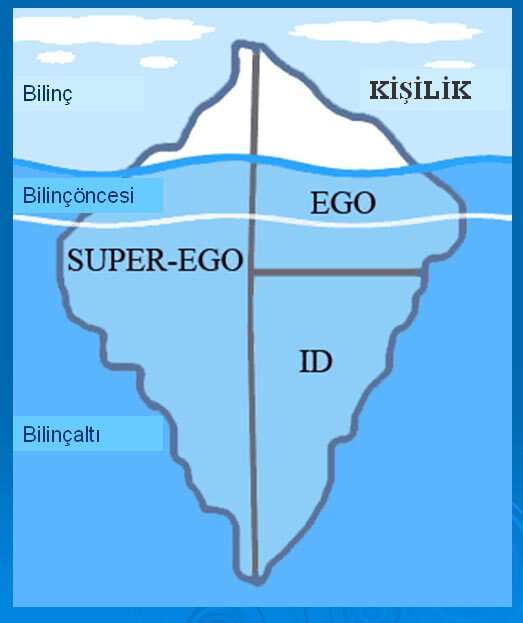

The psychologist Sigmund Freud explored this phenomenon through his theory of the human psyche, dividing it into three components: the id, ego, and superego. These components work together to influence human behavior and emotions:

- The Id:

- Represents the primal, instinctual part of the psyche.

- Operates on the pleasure principle, seeking immediate gratification for desires and needs, such as happiness and joy.

- Is inherently selfish and unconcerned with societal norms or consequences.

- The Ego:

- Acts as the rational, conscious part of the psyche.

- Balances the desires of the id with the constraints of reality and societal expectations.

- Manages inner emotions and helps navigate social constructs by aligning personal happiness with acceptable behavior.

- The Superego:

- Represents the moral conscience and internalized societal rules.

- Often in conflict with the id, as it strives for ideal behavior that aligns with cultural and ethical standards.

- Influences feelings like guilt or pride, shaped heavily by social constructs.

Freud’s framework suggests that the “I, Me, Myself” is a reflection of the ego’s negotiation between personal desires and societal expectations. Emotional states such as happiness, anger, and joy emerge as responses to this dynamic interplay. While our inner emotions may feel personal, they are often deeply rooted in the cultural and social frameworks in which we exist. We tend to think that the disabled – the less abled in some aspects of life are not influenced by this, and somehow, we tend to go into that social, medical, generous model of support.

While these emotions and feelings are valid, time and time again, to quote psychologists there are false premises that we as individuals have or keep.

Psychosis and disabled people

The Charity, Mind UK refers to Psychosis as Psychosis (also called a ‘psychotic experience’ or ‘psychotic episode’) is when you perceive or interpret reality in a very different way from people around you. Applying this to our study, it seems humanity may have entered an episodic state, failing to recognize that disabled individuals are human beings, equal in dignity and worth, rather than perceiving them as separate entities. Why?

Why, what, who and where?

Different traditions can have different contexts, but it is the WHO we are interested it in and why? One Reason is power, another reason could be fear, but more importantly it seems like that our emotions are dominated who we are. Yesterday, we had a discussion with someone, who says you and I share the same values, but it might not reflect others? While Freud’s work has been criticized as unscientific in modern psychology, it still offers valuable insights into the interplay between emotions, power, and societal constructs.

Toward a New Understanding

If we aim to break free from this episodic state, we must move beyond outdated perceptions and biases. Recognizing disabled individuals as integral members of our shared humanity requires re-examining the emotions, constructs, and power dynamics that shape our worldview. Only by doing so can we build a society that values equality, inclusivity, and mutual respect.

![WhoCares_BlackRed1[1]](https://gbgoodwillmovement.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/WhoCares_BlackRed11-1052x406.gif)